South Melbourne’s Bernie Jeffrey is a 'Man Mountain', not only by nickname but in every sense of the word.

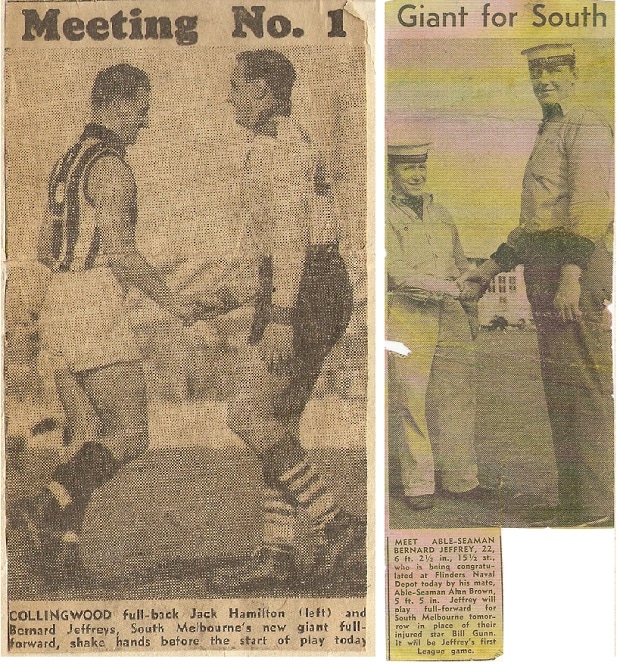

Measuring 6’4” and 16 stone in the old scale – “I’ve shrunk a bit since then,” he laughed – the then 22-year-old was touted as the answer to South’s goal kicking prayers during the early to mid-1950s.

He was also a coregous able-seaman who served with the Fleet Air Arm in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) in the Korean War (1951-52) and Vietnam War (1962-73) and the lesser known Malayan Emergency (1950-60) and Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation (1963-66).

“Who will be South Melbourne’s full-forward?” The Argus probed on the eve of the 1956 VFL season. “Bob Pratt (Jnr) or Bernard Jeffrey?”

It was a toss of the coin at Lake Oval. The proven and fleet-footed Pratt, who some said could “gain a yard on others in three”, had booted six goals in a practice match a few days earlier and was fancied to follow on from his 1955 debut season.

Jeffrey, who first came across Souths’ radar as a 17-year-old, had kicked five in the same game and was considered “League material” possessing “safe hands, cool judgement, and is a long and accurate kick”.

“I used to get big write-ups in the papers, mainly because I was unusual,” Jeffrey said.

“I probably would have got better with more games under my belt – I could mark over anybody and I was pretty fast for my size.

“I was quite well-known in the navy as well. For my first game even my admirals came down and watched.”

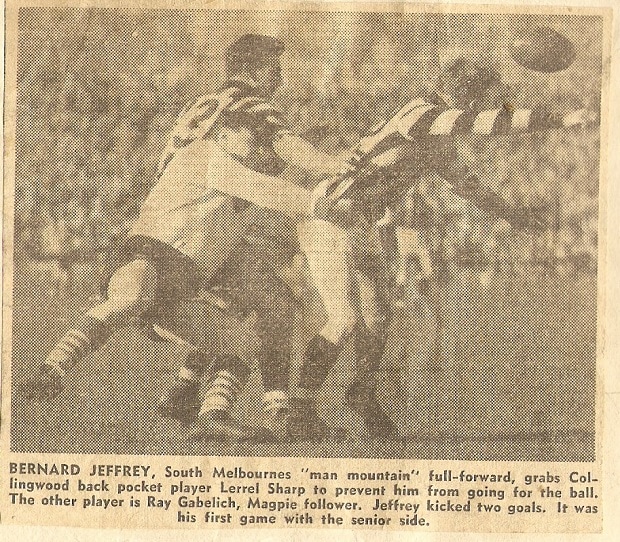

Jeffrey debuted against Collingwood in the opening round of ’56. The first-gamer finished with two goals “and had a hand in several others” according to The Argus despite having Pies’ full-back Jack Hamilton on his tail all afternoon.

Hamilton, with 126 games of experience and who was known as a tough and ruthless defender, shook hands with Jeffrey after the jelly-legged forward marked and goaled with his first kick in league football.

“Jack came over and congratulated me – ‘good kick, Bernie’ he said,” Jeffrey recalled.

“We all called each other by first name, that’s how it was in those days. We played tough and still knocked each other around but there was always that respect.”

Despite all the hype surrounding his form with St Kilda’s Under 19’s and the RAN's own football side, four years would pass before Jeffrey’s debut which now might seem like a discredit to a talent pronounced as “one out of the box” by South officials at the time.

But Jeffrey was bound to the RAN, a post embraced on his 18th birthday and held close to his heart for the next 27 years.

Newspaper articles between 1951 and 1955 reported this athletic monster on South’s list who would dominate the training track and practice matches, causing a stir not only with South's dressing room but around the football-loving inner dwellings of post-WW2 Melbourne.

But in a period of unwavering unrest, duty would call time and again which meant Jeffrey remained wrapped up until that day against the Magpies.

He managed another three matches until duty would call again and definitively cut his promising football career short.

“I always wanted to play football,” Jeffrey said.

“And I was lucky enough to play a few games and kick a few goals and enjoy some time on South’s list - I even got a kick playing with the RAN at different stages.

“But I also always wanted to join the navy. We grew up during WW2, I had family and close friends in the navy and army, and growing up near the port I believed it was the right thing to do.”

Aboard aircraft carriers the HMAS Sydney, HMAS Melbourne and HMAS Vengeance, Jeffrey was away from the calamity of the front line. But, as for many of the young men and women who served in times of conflict, Jeffrey was never totally blanketed from its horror and atrocities.

“I saw a lot of tragedy,” he said.

“I was only young during the Korean War and saw some terrible things like when I went ashore with some Turkish commandoes after the Battle of Inchon.

“And when we were anchored off the shores of Japan we were only some 17 miles from Hiroshima. We went up there a couple of times and saw the devastation left behind from WW2.

"There was nothing left, people were covered in sores and rashes and scars from burns. The devastation was everywhere, it was just so sad."

Jeffrey has suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder since his military discharge in 1978. Breaking down in tears in the shadow of his haunted past is still a daily occurrence.

“I still think about it,” he said. “I’m what they call a TPI (Totally and Permanently Incapacitated ex-serviceperson).”

In the darkness of his own battle scars, Jeffrey has lived a long and happy life. It has been a life largely spent supporting his beloved Swans from his home in Queensland and making up for lost time with son Stephen.

Bernie had not seen Stephen for 29 years before the pair reunited in 1986.

“Such was life in the navy,” Jeffrey said.

"His mother was English and took him back, only to return and never tell me. I was on the next plane to Western Australia the day he called me…it was really emotional.

"He was a dead-set ringer of me.”

Beneath the emotion creeping into Jeffrey’s voice as today's plans were unveiled, which included laying a wreath in honour of his fallen comrades at his local Anzac Day Service, there’s an unmistakable pride in his service to the RAN and his on-field feats.

There is also not one ounce of regret or lingering questions of ‘what if?’ on his short lived football career and what could have become of his stature and potential.

For that, Bernard Jeffrey is and will forever be a 'Man Mountain' - not only by nickname but in every sense of the word.