Elkin Reilly feels at ease with playing, in his own words, a handful of “useful” games for South Melbourne.

His career as South’s ruckman between 1962 and 1967 was modest, enough to keep him around for 51 games and the coaches happy, but enduringly significant.

Little did anyone know at the time, Reilly, one of the Swans’ earliest Indigenous footballers, would leave a lasting imprint on the more welcoming and accepting game we love today.

Early life

Born in the Northern Territory community of Alpurrurulam (or Lake Nash Station in the common tongue), a severely malnourished Reilly became a child of the ‘Stolen Generation’ and was taken away from his mother shortly after birth.

Reilly’s voice softened as that period of his life was touched on.

“I have never been back,” describing his rural birth place situated on the Northern Territory-Queensland about 600km east of Tennant Creek.

“There is a bit of a vacuum there but obviously I was too young to remember all that so it’s hard to feel any attachment.

“I’m just annoyed because I never met my mother, or father, just a few relatives. As far as I know I only had the one brother but he died in a car smash.

“I have been to his gravesite but that’s about it.”

Reilly was transferred to Alice Springs Hospital then to the local Bungalow, or Telegraph Station, where Dr Pat Reilly of the Royal Flying Doctors Service took the toddler under his wing.

Courage through football.

Reilly moved to Adelaide and, under the care of foster parents Pat and wife Betty, Reilly enjoyed a comfortable upbringing and what ultimately proved a life-changing education at Rostrevor College.

“I was no good academically,” Reilly conceded. “But sport gave me confidence, made me feel accepted and was one of the main things that pulled me through life.”

Reilly the sportsman excelled. His height – around six foot in the old scale – abled him to become a state high jump champion and handy footballer for the school’s first XVIII.

After school and 12 months of national service, Reilly persisted with football and played for country clubs in South Australia before a brief stint with Wentworth Football Club in south-west NSW put Reilly’s talents in front of three Melbourne-based recruiters.

“I received an offer from Essendon who were the top team at the time,” Reilly said.

“I worked it out pretty quickly I was never getting a game because Geoff Leek was the gun ruckman at the time. Then Richmond came along but the top ruckmen there were Neville Crowe and Mike Patterson, they were just starting to blossom.

“South Melbourne also happened to be there and I said to myself 'I have a chance here' as Jim Taylor was the number one ruckman and he was just about to retire so I went down to give it a crack.”

Reilly was eased into VFL football. One of only a few Indigenous players at the time, the 191cm ruckman spent three quarters on the bench during his Round 5 debut before waiting three weeks for another opportunity.

“I realised during my first game I’d have to lift my tempo," he laughed.

And Reilly did, playing a full game on Geelong’s John Yeates at Kardinia Park in Round 8. South might have went down 6.8 (44) to 9.8 (64) but Reilly was happy with his effort against the Cats’ captain.

Reilly played with and against some of the greats of the game, the greatest of all his eyes however was none other than teammate and skipper Bob Skilton.

The Reilly/Skilton combination was described by one tabloid as a shining light in a rather dark time for the struggling Bloods.

“Bob always knew where the ball was going,” Reilly recalled.

“Bob was one of the few rovers who could collect the ball in one stride and be out of reach in the next, before anyone knew what hit them.

“He was the greatest player I have ever seen and I’m honoured to have contributed in one way or another to his career.”

A career gone but not forgotten.

Reilly was oblivious at the time but his appendix ruptured ahead of the 1967 season. The ruckman, coming off 13 games the previous season, tried to battle through the discomfort but a form slump prompted South officials to make a tough call.

Reilly’s last game was against Richmond at Lake Oval – it ended in a heartbreaking one-point loss.

Since retiring from football, Reilly’s impact not only on the South Melbourne/Sydney Swans Football Club but on the AFL has been everlasting and, with the help of many others, history shaping.

Reilly was among the first who cut the tape and broke down the barriers, fighting through a trying time for Indigenous people which extended beyond the white lines on a football field.

“I experienced racial vilification once when I was playing,” Reilly said.

“What made it easier for me when I was at South were the people. They made me feel comfortable and not threatened which was a big thing back in those days.

“They made me feel wanted.”

Legacy.

Reilly can be classed among those who today's comparable Adam Goodes describes as "trailblazers".

The likes of Joe Johnson (Fitzroy) and Percy Jackson (North Melbourne) laid the foundations before Reilly's time, while those of the Graham “Polly” Farmer (Geelong), Syd Jackson (Carlton), Barry Cable (North Melbourne) and Maurice Rioli (Richmond) ilk kept the momentum going.

Then came Michael Long (Essendon), Nicky Winmar (St Kilda) and alike who openly helped change the AFL for the better and into the game we know and love today.

Today’s stars like Goodes, Lance Franklin and Lewis Jetta – who all took centre stage in Friday night's Indigenous Round opener – are no doubt thankful for those who took a stance to allow them to perform in front of and thrill Swans supporters far and wide.

Reilly added: “I didn’t really think about it at the time, but I guess you can say I was one of the pioneers in the South Melbourne side in terms of Indigenous footballers.”

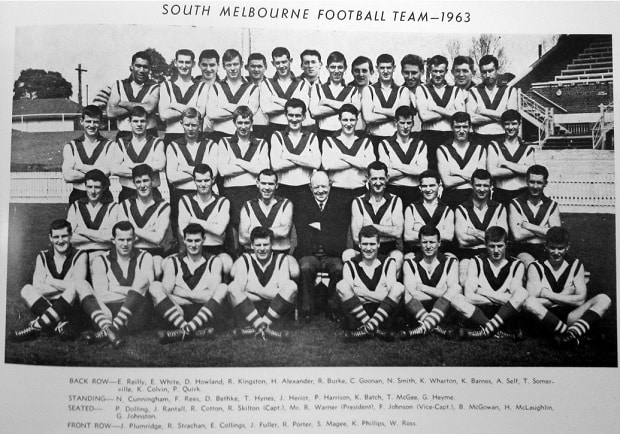

Elkin Reilly (back row, far left) alongside teammates ahead of the 1963 VFL season.